Creating Sanguine

I first made Sanguine in 2020. That year I was troubled by just about everything, minus a certain disease. Out of all these troubles, the biggest was a single feeling. That being the feeling of lacking an identity. It wasn't a total lack of self; I knew what I loved, but I didn't know how to present that to the world. Every time I tried to cobble something together, it led to more questions than answers. I’d describe it as a form of selective mutism, where I’d lock up and retreat into myself at seemingly random moments. I knew better than to imitate others, but I struggled nonetheless. Sanguine was my latest attempt at closure and miraculously, they landed straight into my heart. I consider introspection a virtue, and moments like this are why. A year later, I worked through our gender, and Sanguine evolved with me. In their completed form, Sanguine is a mirror of myself, only exaggerated to comedic effect. My friends know me as affectionate and conscientious to a fault, while Sanguine is a nervous wreck. Thus, they serve less as a power fantasy and more as a performance of self-awareness.

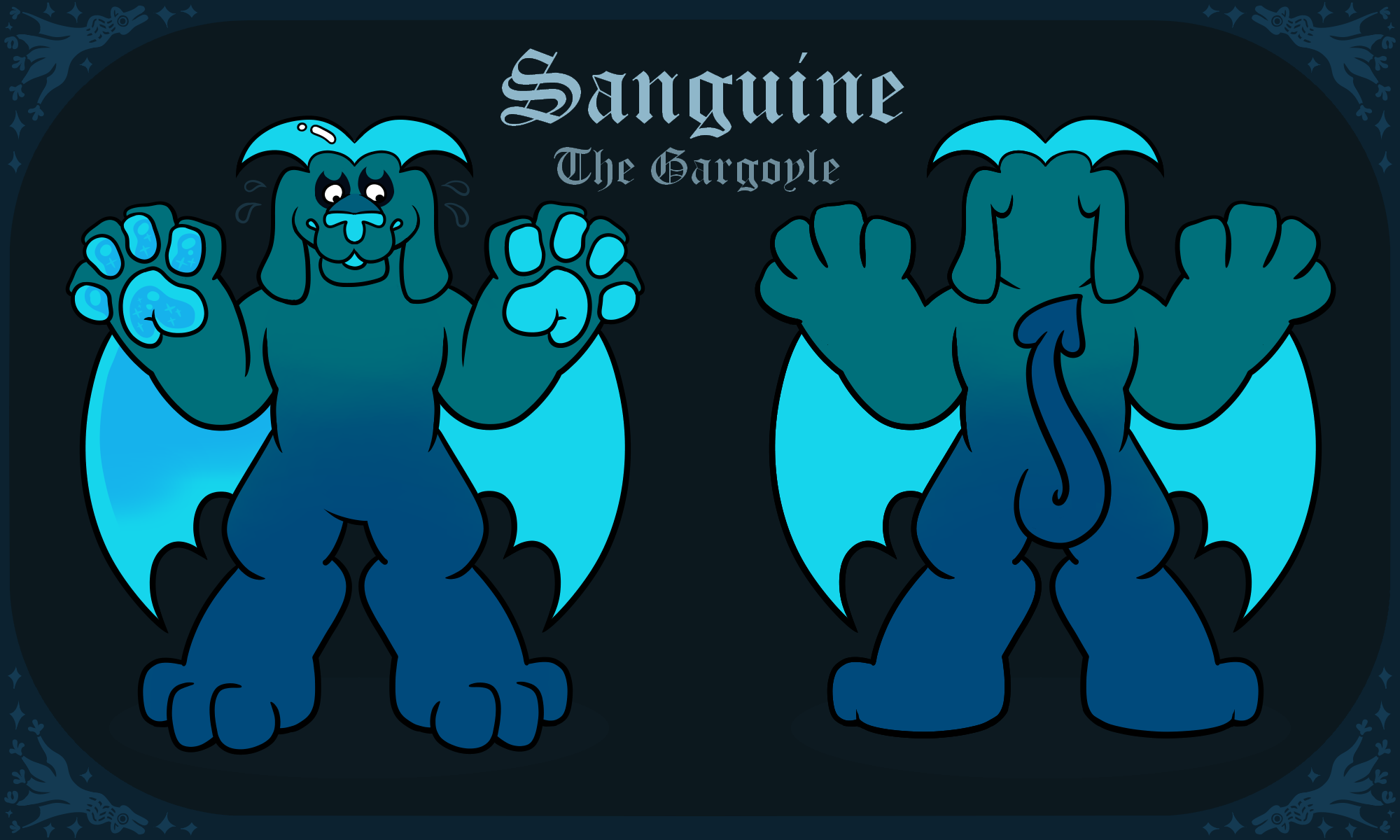

This even shows in their very design. Blue was chosen for my pre-dawn motif and its typical link to human sadness. Their horns are not a proud crown of bone and keratin; instead, they point forlornly downward. Their eye markings furrow their brow into a constant look of gloom. Combined with their horn shape, they carry the air of a depressed court jester. Their ears, once sharper in earlier designs, are now lopped and soft to the touch. Their face is catlike, closer to a small cat than a lion; so the poor thing can't even roar. They don’t have claws, but large, plushlike paws. Seldom is there a sharp edge on this beast, softened by its blobby contours and heart-shaped tail. In short, they're designed to look absolutely pitiful. Their name came from a line in our favourite childhood video game; the Elder Scrolls IV Oblivion. Amongst the game's more law-abiding guilds, the player can initiate into an assassins’ guild. When they complete the guild's initiation quest, they're led to a dilapitated house in one of the game's major cities. Once inside the house, the player needs to go downstairs and speak to a magical door, which riddles “What is the colour of night?”. To this, the player must respond “Sanguine, my brother”. Sanguine in that context is likely a reference to blood, but in the context of naming this Sanguine, it comes with a double meaning. Sanguine’s skin is a mix of the colours Pearl Night blue and Pearl Gentian. So alongside the prior allusion to blood, this Sanguine is also the colour of night. Although, the word Sanguine can also describe an absurd sort of optimism, which matches about as well as me and broad daylight.

___ /\/\ ___

/ _ \(o__o)/ _ \

\/ \_(;;;;)_/ \/

__________M__M_________

(_)___________________(_)

|*| __ __ .' |*|

|*| / \ / \ .'|*|

|*| \/\ \/ /\/ .'|*|

|*| (o/ o \ |*|

|*| .' / Y ::\ \/ |*|

|*| \__\__/ | '. |*|

|*| '. | |_/ | .' |*|

|*| ____ \_/ \____|*|

|*| ( |*|

|*|/ / |*|

|*| __\ \ |*|

|*|( ) __/____|*|

|*| 0 a 0 ( _ _ |*|

|*|__\000 ___(__(__(__|*|

(_)_ _(_)

| S A N G U I N E |

|_________________|

Depicting Sanguine

But what would this page be without reference material? This section is mainly for any artists I commission, but it can be a fun trivia bit as well. I'm hopelessly spellbound by the list format, so here we go:

- They’re an ethereal entity, psychically projected from the dreams of their corresponding (and identical) statue. Physical flesh, blood and other such attributes are absent. It explains all the sparkling and glowing; which is most visible on their nose, horns and pawpads. It's like a glow-in-the-dark effect.

- Like many grotesques (and after some wondering) they are toothless. They used to have teeth but they're gone until further notice.

- Sanguine can wear clothes, but would most like the company of oversized jumpers and ghost-themed pyjamas.

- Sanguine can nurse a glass of warm milk, a vial of pond water or apple juice served in the skull of an enemy. If you're feeling devious, you may depict Sanguine with a block of cheese.

- Sanguine likes to haunt crypts, chapels, cathedrals, woodlands and anything else of that sort.

- Sanguine is too nervous to speak but can compromise by scrawling on chalk boards.

- Tail posture follows cat rules; curled when happy, tucked when afraid and vibrating/thumping when annoyed. Although you may notice, they like making it go all over the place.

Whatever you come up with, all Sanguine asks is that you do your best.

The thematics of grotesques

I identify with grotesques for my love of chimères and Gothic art. I adore vampires, but I don't see myself as one. I'd say I'm an onlooker, a prop to the vampire set. Their bombastic personalities and lurid backstories, while fun to watch, clash with my own. Instead, I'm more akin to a Castlevania enemy or a creature you'd see in a 70's toy line. It's modest, and some may say overly so, but it's right for me. Also note the absence of "fursona", "furry" or even "funny animal" as I speak. Sanguine and I are furry-adjacent at most. Back when I was a furry, I couldn't relate to other furries. I felt like something else.

The main appeal of the grotesque, like other chimères, is its sheer versatility. There are no real rules, and surprisingly, not all grotesques befit their name. One atop the Château de Pierrefonds depicts a mother cat holding her kitten, thus showing the grotesque as an exercise in cuteness. They can be quadruped or bipedal, sapient or feral, gendered or ambiguous. They can mean anything an author wants them to mean. How one must wonder what it feels to be one that hates its own shape, or yearns to feel living flesh?

In the 1997 book "Holy Terrors, Gargoyles on Medieval buildings", Janetta Rebold Benson theorises about the grotesques of medieval europe. Her first theory suggests they symbolise the creatures of hell.

"It is possible that members of the medieval Church recognized the potential of gargoyles to in-trigue, to entice, to attract attention and perhaps even attendance. The medieval preference for grotesque gargoyles is clear; they far outnumber the comparatively few realistic depictions of humans or animals. The frequently monstrous nature of gargoyles makes obvious that all medieval art was not intended to be beautiful. In fact, ugliness had a fascination all its own, and images of the macabre were very much a part of daily life in the Middle Ages.

Because it is extremely unlikely that there is one meaning for all gargoyles; various interpretations must be surveyed. Some are of limited plausibility, such as the suggestion that gargoyles were inspired by the excavations of skeletal remains of dinosaurs and prehistoric beasts, or that gargoyles were derived from the constellations. Rather, the key that unlocks all discussion about the meaning of gargoyles seems to be the great concerns about sin and salvation that prevailed during the Middle Ages. The preoccupation of many medieval Christians with the eternal fate of their souls, coupled with widespread illiteracy and the consequent emphasis on the instructional use of visual imagery, resulted in the creation of many monsters in medieval art. Evil was both an abstract idea and a concrete fact something very real that could be given visual form by artists."

- Benson, 1997, p.23-24

Writing a century prior, Abbé Auber and Ludwig Gerlach suggested another idea. Where Benson describes visual shorthands for evil, Auber describes man's triumph over it. These demons, once wild and free to terrorise men, are domesticated servants of the church. For the French folklorist, this will conjure images of La Gargouille: the scourge of Rouen and its eventual war-trophy. The dragon's neck, once the passage of many hapless maidens, was too hardy to burn. Thus, it found itself mounted on the church walls as a warning to other creatures. Yet the inverse could be true. Instead of being bound to the church, the grotesques are being driven from it in a mass exorcism. However, this idea is ambiguous; it does not clarify whether they serve as a reminder of the Church’s power or of its initial consecration. Gerlach and Auber also disagreed on the importance of this exorcism, as explained by the latter:

"Although I concur with the idea that gargoyles visualize the cleansing power of the church through exorcism, the cleansing force of the Church's sacraments and the force of prayer should also be added. The petrification, to my mind, is not significant, but was a mere side-effect of visualizing how a strong ecclesia, community of the faithful, could expel all evil."

- Auber, 1871

Benson nears this theory, but alludes to a long-standing folkloric motif. That grotesques, despite their monstrous appearance, are man-made sentinels. Like dried cats, immured shoes and witch-bottles, their presence is not a display of dominion. They're secretive, but in their numbers they paralyse lurking threats with hundreds of eyes.

"Perhaps grotesque gargoyles were intended as guardians of the church, magic signs to ward off the devil. Amalgamations of animals have long been used by artists and authors to create frightening images. This interpretation would justify making a gargoyle as ugly as possible, as a sort of sacred scarecrow to frighten the devil away, preserving those inside in safety, Or perhaps gargoyles were themselves symbols of the evil forces such as temptations and sins— lurking outside the sanctuary of the church; upon passing the gargoyles, the visitor's safety was assured within the church."

- Benson, 1997, p.24

This reminds me of the Church Grim. A Church Grim, in contrast to the grotesque, is not a demon or sign of evil. Instead, a Church Grim is said to be the ghost of a dog, buried alive in the foundations of a church to guard it eternally. Unlike other black dogs, it's explicitly christian and actively protects its land against acts of sacrilege. Despite their differences, grotesques, Church Grims, and the mounted head of La Gargouille all serve as symbols of sacrifice. By dying or remaining in servitude, they become a monstrous echo of the original Crucifixion.

Alongside Christian analysis, other texts suggest more secular reasons for the grotesque. In a November 1912 edition of the Arts & Decoration Magazine, one of its writers G. Mortimer Mark, discusses this concept.

"For the grotesque is always an architectural surprise, besides being an architectural joke. It grins down at us from a safe and unexpected perch overhead, high up on a column, or leers out from the shadow of a balcony or overhang, with varied multiplicity of facial contortion. It is obvious that the grotesque in architecture must be sparingly and judiciously used- being essentially humorous, it must realize that brevity is the soul of wit, and that if too much in evidence, it could be as tiresome as the man who is never serious. "

- Mortimer, 1912, p.22-23

Given many gargoyles exist as naked men spewing torrents of rainwater from their buttocks, this is more than plausible. One atop the Salisbury cathedral in England spends its time nibbling the cheek of another, who screeches in silent torment. The aforementioned mother cat clutches a kitten, and is hardly a portent of any kind. If the hard work of a sculptor can't be adequately rewarded in financial compensation, they can still take amusement from their creations. Another proponent of this theory is ex-president Theodore Roosevelt, as seen in his review of the 1913 Armory Show.

"The makers of the gargoyles knew very well that the gargoyles did not represent what was most important in the Gothic cathedrals. They stood for just a little point of grotesque reaction against, and relief from, the tremendous elemental vastness and grandeur of the Houses of God. They were imps, sinister and comic, grim and yet futile, and they fitted admirably into the framework of the theology that found its expression in the towering and wonderful piles which they ornamented."

- Theodore Roosevelt, 1913

This theory of levity is unique, and to ignore its humanity would be a display of ignorance. The people of this time believed in hell, and bearing that weight daily would fill the mind with its own demons. A peering face might bring mirth to both its sculptor and the overworked onlookers below. Even the most devout, much like their counterparts today, could not have been overly certain of their afterlives. While their prayer commences, it happens amidst the company of grotesques. Choir stalls, corbels, doorways, misericords and rood screens seldom stand unadorned. Why should a potential sinner let their eyes rest away from God onto a dreary corner? Why not remember the perils of sloth, through a piteous, slavering creature peering back at them from the gloom? It's a reminder of evil, yet a reprieve from the oppressive dogma that so defined the time. These misshapen creatures, as absurd and unwelcome as they look, frighten things more frightful than external “ugliness”. I designed Sanguine, beneath the sensory and aesthetic appeal, to protect myself from the riptides of dissociation and self-doubt. Evil spirits in their own way.